Leading Communities in the Second Machine Age

Throughout history, technology has presented us with new ways of seeing and adapting to the world, enlightening the human condition during difficult times. Our technological prowess gave us agriculture, which allowed humanity to cluster into cities. You know the story from there; concrete, trains, steel, and automobiles are just some of the innovations of the First Machine Age that have allowed us to build bigger and further than we ever dreamed of.

Yet despite all of the dazzling innovations that we’ve produced, deep problems persist. New, unforeseen social and economic difficulties often arise, resulting from the latest mode of transportation or shiny gadget that promises us universal progress. This push and pull is apparent across all aspects of our society, but the duality of who benefits from new technology especially comes to a forefront in terms of how we plan, design, and build our cities.

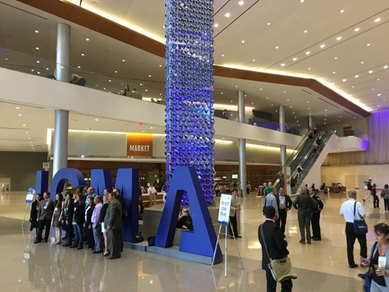

I recently had the opportunity to speak on this topic during the 2017 International City/County Management Association (ICMA) Conference in San Antonio—the largest annual event in the world for local government managers and staff. Lee Feldman, City Manager of Fort Lauderdale, outgoing President of the ICMA, Jim Keene, City Manager of Palo Alto, and myself posed this question: how can local government lead communities during the “Second Machine Age”?

What exactly is the Second Machine Age? The name refers to a book by MIT researchers Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee. They postulate that whereas the First Machine Age, or Industrial Revolution, involved the mechanization of physical labor, a new Second Machine Age, or Fourth Industrial Revolution, is rising out of an array of digital technologies. This new era built on previous decades of progress in computation involves the automation of many cognitive and physical tasks formerly mastered by humans. Smartphones, machine learning, driverless cars, and advances in autonomous robots are evidence of this new period in history, as noted recently by the Washington Post’s article The Fourth Industrial Revolution is Upon Us.

Just as the Industrial Revolution transformed our society and reshaped our cities, the Second Machine Age is presenting us with radical disruptions—perhaps even greater than those from the past. Skyscrapers and steel allowed us to capitalize on land values but sometimes diminished the human scale that our most cherished urban areas embrace. Automobiles drove us towards a new definition of the American Dream, but also presented us with pollution and adverse health impacts. Because cognitive abilities are essentially what makes us human, the realization that machines will increasingly mirror human cognition will have vast repercussions for society, as Brynjolfsson and McAfee also note in their book, Race Against the Machine.

As designers and planners, we are interested in how we can lead the change not only in shaping the built environment, but also by anticipating the macro-level disruptions that are beyond the grasp of any one individual. We must continually ask what opportunities and challenges might be associated with the rise of computing and cognitive automation?

In the case of driverless cars, there is great potential to turn spaces formerly devoted to automobiles back into pedestrian-friendly environments. Yet questions remain. How long will it take to implement these technologies to their full potential? Will the adoption of these technologies and the impacts on our cities be equitable? In an age where digital-network effects create a bigger-is-better and winner-take-all economy, how do we create incentives that ensure technology is used for the greater good? As technological progress follows its exponential curve, how will its effects on our culture and economy reshape how we live in cities?

Artificial intelligence and other technologies seem poised to disrupt the job market and economy, perhaps contributing to the economic theory of technological deflation (as noted recently by the investment firm Vanguard). These disruptions point to a future of rising inequality and places where the traditional American relationship between city and suburb, and Central Business District and residential neighborhood, are no longer as clear as they once were.

How do we solve the problems we’re currently facing as a result of the nascent Second Machine Age, while preparing for the ones ahead? It’s a difficult question – one that the three of us struggled to address, while considering great feedback from the audience. A few things are certain. No individual can address this alone; it will take a concerted effort at state, local, and federal levels, along with participation from the private sector. And because these are uniquely human problems—we are still the only being capable of ethical and emotional intelligence—the path forward will also require a global understanding and approach.

Technology may already be contributing to a more unequal society as noted by Vanguard – where productivity continues to rise but jobs and wages stagnate. And the effects of inequality are readily apparent in the United States, as the United Nations’ Philip Alston recently wrapped up a two-week journeythrough American cities and suburbs, documenting extreme poverty. Alston notes that “The United States is one of the world’s richest, most powerful and technologically innovative countries; but neither its wealth nor its power nor its technology is being harnessed to address the situation in which 40 million people continue to live in poverty.”

The Urban Land Institute recently published a book on “Building Equitable Cities,” a central tenet of city building in this new era. The book points out two strategies, place-based and people-based, to help reduce inequality and create more cohesive places. The book highlights several place-based strategies already put in place by communities in Atlanta and Tysons Corner to help promote affordable housing, increase mobility options, and emphasize educational opportunities.

Designers and planners may feel that some of these issues are beyond their scope. That is not the case. We must be aware that unchecked technological innovation has the potential to erode our humanity. We must actively assess and use our technological resources to help us design our cities and buildings to celebrate the human scale and the essence of what it means to be a human being.

Our work must be inspiring and innovative, but it must also embrace social equity and our responsibility to promote inclusive communities. Urbanist Richard Florida kicked off the ICMA conference in San Antonio, emphasizing that cities and regions embrace strategies that promote inclusivity rather than “winner-take-all urbanism.” To me, the importance of noting that we are all in this together is no more apparent than in scientist Carl Sagan’s “Pale Blue Dot” quote, where he emphasizes that the smallness of our planet within the scale of the Universe “underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known.”